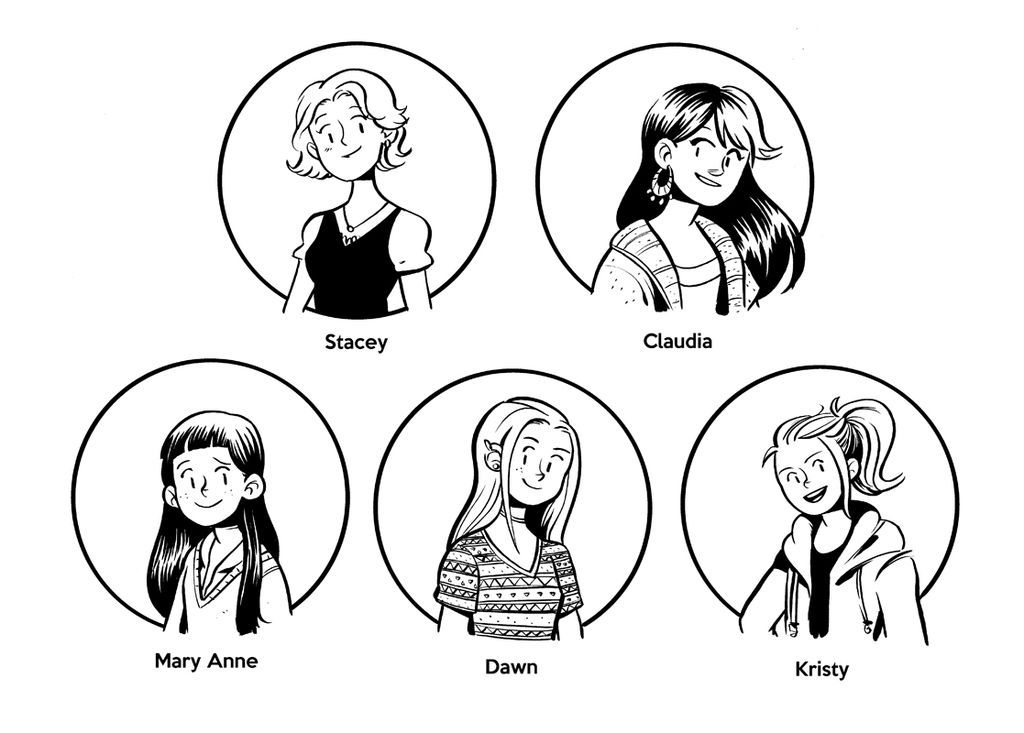

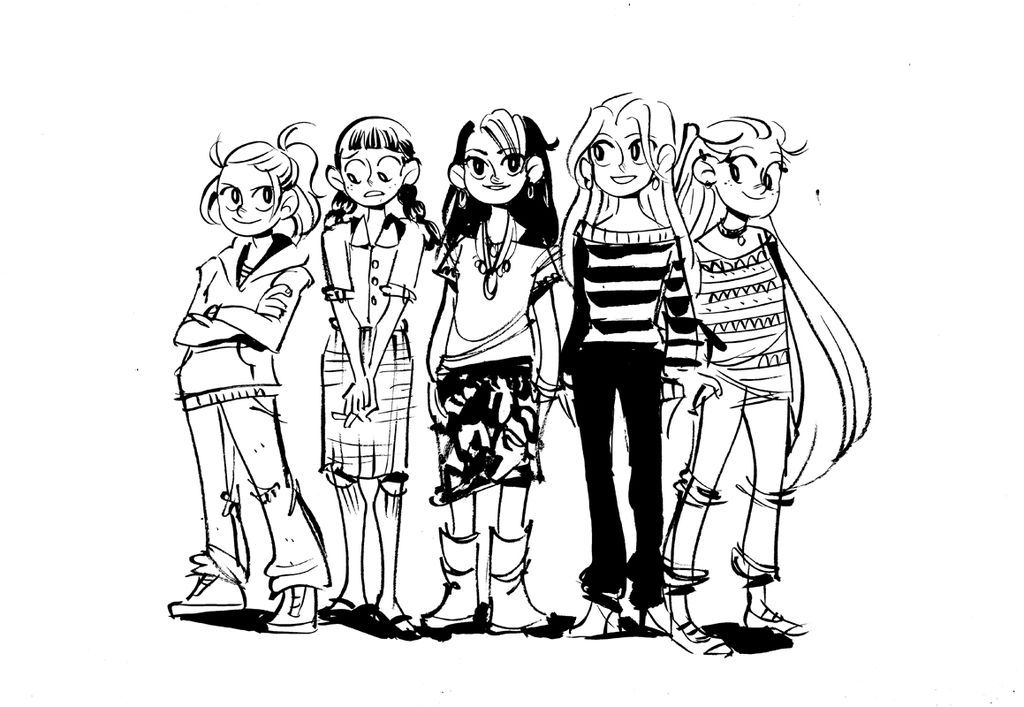

Since then, the books have been repackaged and resold in various ways. They were updated in the 2010s, with new covers, some updated content, and a new prequel, The Summer Before. The most recent repackaging of the books occurred just this year, coinciding with the release of the new Netflix series. All told, there are about 180 million BSC books in print. In this article, I explore specifically how one of those particular iterations of print BSC are made: the BSC graphic novel. Graphic novels are yet another way the books have been repackaged for new audiences. When Scholastic launched their graphic novels imprint, Graphix, the BSC books were adapted to this new format. The first four BSC graphic novels were adapted by Raina Telgemeier, herself a BSC fan. The first book in the series and the first graphic novel adaptation, Kristy’s Great Idea, was released in 2006. These first four graphic novels were black and white, and they were a huge thrill—they were the first new BSC in six years! Several years later, beginning in 2015, the graphic novels were released in colour editions after editors at Scholastic realised readers preferred colour. The BSC graphic novels are now up to eight books, the first four adapted by Telgemeier and the second four by Gale Galligan. The most recent book, Logan Likes Mary Anne, was released in September 2020, and it was this book that sparked some questions for me about how the graphic novels were adapted: why was this one the latest book to be adapted? Who chose that? Why was Jessi introduced now? Why was Logan Southeast Asian*? How do you actually turn a children’s novel into a graphic novel? Happily, I found some willing people at Scholastic who could answer my questions and reveal exactly how the graphic novels are made—a more specific explanation of one of the ways in which the series has been delivered to fans. The adaptation process is a collaborative effort that includes the artists, Scholastic editors, and Ann M. Martin. Choosing which books to adapt is a group effort, and the graphic novels stay quite close and true to the original novels, with some updates for a contemporary audience. Each artist is given freedom to create the artwork in their own style. Cassandra Pelham Fulton, Editorial Director of Graphix, reveals: ‘As big fans of the series and brilliant cartoonists, Raina and Gale always had an excellent handle on what should be included in their adaptations.’ Fulton elaborates on the process: ‘The adapter starts with a copy of the original novel and makes notes on what they’d like to include in their adaptation. Much of Ann’s text appears in the graphic novel as it does in the original novel, just as much of it is adapted and edited for the comics format and present-day audience. Once we all agree on what should go in the adaptation, the adapter proceeds with thumbnailing, penciling, and inking the book. The inked pages then go to our awesome series colorist, Braden Lamb. He adds the color, and then it’s just finishing touches from there! Gale and Raina are friends and industry colleagues, and I know that they’ve talked about working on the series.’ Apart from the technical details of adapting a BSC novel, there is an emotional aspect too. Both Telgemeier and Galligan were childhood fans of the BSC, and Galligan was also a fan of the first graphic novels done by Telgemeier. She reveals the emotional component of doing the graphic novel adaptations: ‘It was a layered feeling for me—I’d absolutely adored the Baby-Sitters Club growing up, and then fell in love with Raina Telgemeier’s work a decade later, so being asked to follow in Raina’s footsteps while also adapting this story I had such fond memories of was very exciting and intimidating.’ She expands on the emotional rewards from doing the adaptations: ‘One of my favorite memories is from a signing I did alongside Ann M. Martin, where parents would come up and tell Ann, “I’ve loved these books for thirty years, you changed my life,” while at the same time, their children would talk to me about their favorite scenes from the graphic novels. It’s easy as a cartoonist to get caught up in the day-to-day work, but moments like that—they remind me of how stories can bring us together.’ Some of my questions related not to the nitty gritty of novel adaptation, but to character and story changes, such as why Jessi was introduced in Logan Likes Mary Anne, which is several books earlier in the graphic novels than in the original series. Fulton explains, ‘Mallory was introduced as a junior member a bit early during Raina’s run on the graphic novels, so naturally Jessi, who becomes Mallory’s best friend, was also introduced a bit sooner.’ Another question I had related to the ethnicity of certain characters. In the original books, an emphasis is made on Jessi being Black, and her family being one of the few Black families in Stoneybrook. In the graphic novels, several characters and families are depicted as Black who are Caucasian in the original books (either explicitly stated or seen in cover illustrations). Gale, the artist of these books, took the lead in designing the characters, but the overall premise of greater diversity in these new forms of BSC is something embraced by Ann and the Scholastic team. David Levithan, VP/Publisher and Editorial Director of Scholastic, explains, ‘When revisiting the BSC in any form—whether it’s the repackagings or the graphic novels or the TV show—we absolutely want them to be reflective of the world today. The Baby-Sitters Club was viewed as very inclusive when it launched in the 1980s, but now there is rightfully a different standard of inclusivity, and we want to make sure that we are in step. I think when any of us, including Ann, envision what Stoneybrook would be like now, there’s absolutely a wider range of identities and cultures than there were forty years ago.’ In updating the books for a new generation, it was not only technology that was updated, but Stoneybrook was too. This last point is actually what swayed me from my initial hesitation towards some of the new graphic novels. I have loved the BSC for almost 30 years, and I feel like I know Stoneybrook in the same way that I know the suburbs where I grew up: intimately, like a local. And I felt like I knew the characters, not only the BSC members but also their schoolmates and families they babysat for. I had (and have) a very strong and clear mental image of what the series is. When the graphic novels first came out in 2006, my reaction was a mixture of ‘oh my gosh new BSC must have this is dibbly fresh’ and ‘but what if they ruin it and it looks nothing like what I picture?’ When you repackage the BSC to deliver it to old fans in different ways and also try to reach new audiences, how do you balance sticking to canon with knowing that some things will be missed or changed? Happily, they lived up to my high hopes and the BSC experience was enhanced, not ruined. Fast forward to now, and to the last few graphic novels that were adapted by Galligan. In these ones, Logan Bruno, the Perkins family, the Fieldings family, Alex and Toby from Sea City, Austin Bentley, and Cam Geary are depicted as people of colour, not Caucasian as in the original books. My first reaction was, ‘This is wrong! That’s not how they’re described in the books!’ This is me being a BSC purist, and wanting any adaptation to be a hundred per cent true to the exact words of the books. Further reflection—and writing this piece—has made me realise that while these adaptations are not exactly the same as the originals (otherwise they may as well just be the originals) and true to the descriptions word-for-word, they are actually 100% true to the spirit of the BSC. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, the BSC was inclusive for the time. It included an African American character, an Asian character, a Jewish character, characters whose parents had divorced. Racism is directly addressed in Keep Out, Claudia! and holidays and occasions like Kwanzaa, Hanukkah, and Bar Mitzvahs are key plot points in various books. But Stoneybrook was still a very Caucasian-dominant town, with very few families and characters of colour. In 2020, inclusivity and diversity standards have changed. America has changed, too. Racial diversity has increased in the past three decades in rural and small town America (particularly in the Hispanic population), and in recent years there have been calls for greater diversity and representation in all forms of media, including in the publishing industry. If the BSC was to stay true to its core, and to its message of the importance of strong communities, the community itself had to be updated too. The graphic novel format is arguably the best way to make this kind of update. Instead of changing the original text and description of characters to account for greater diversity in Stoneybrook, the readers are simply shown that it is there. The original series and Stoneybrook will always have a special place in my heart. No matter how many times the books are repackaged and adapted, there is nothing that can replace my old copies of those books, with their yellowing pages, torn covers, and outdated technology. But I’m very happy to live in a world where there is new BSC too, where these characters and stories can reach a new generation of readers and be as relevant to them as the original ones were to me and countless other readers in the 1980s and 1990s. There are new BSC graphic novels to come, with new artists to take over where Galligan left off—Gabriela Epstein has adapted Claudia and the New Girl for publication in February 2021, and I will be first in line* to get my hands on a copy. *Metaphorical line, given that there is a pandemic and I will most likely be preordering the book, like I have with all the other BSC graphic novels. Need more BSC? We have you covered: The Baby-Sitters Club Graphic Novels: A Guide to More BSC, My Top 21 Baby-Sitters Club Books: A Definitive, Objective, Unbiased Guide, Thirty-Plus Years After Kristy’s Great Idea, What Makes the Baby-Sitters Club Endure?, Shipwrecks and Counterfeit Money: 10 Ridiculous Moments from the Baby-Sitters Club. *Editor’s Note: Logan was incorrectly identified as Black in the original post. This has been corrected.